Nothing Is Impossible

Sukanta Roy, 1977 Electronics & Tele-Communication Engineering.

Arunima Sinha is the world’s first female amputee to scale Mount Everest (Asia), Mount Kilimanjaro (Africa), Mount Elbrus (Europe), Mount Kosciuszko (Australia), Aconcagua (South America), Denali (North America) and Vinson Massif (Antarctica). She is also a volleyball player.

“There’s a small district 200 kilometers outside of Lucknow called Ambedkarnagar. That’s where I am from. My father was an engineer in the army and my mother a supervisor with the health department. He passed away when I was three. I have an elder sister and a little brother. Upon my father’s death, my sister’s husband, whom we fondly call Bhai Sahib, became the family’s de facto patriarch.

Everyone in my family enjoys sports and I was naturally an athletic as a child, though I never had any professional aspirations for the same. I have been cycling since I can remember, loved playing football and was a national level volleyball player. But sports took a backseat when my job hunt started. I studied law after my post-graduation and was confident about getting started on a robust career. But everyone feels the sting of unemployment at some point in their lives. This time I was at its receiving end.

Bhai sahib suggested I apply at the Paramilitary Force in the army, saying that this way I could stay close to my beloved sports while earning a living at the same time. Despite many heartfelt tries, I didn’t get through. The job search was not panning out as I expected and I was getting desperate. In 2011, I applied at CSIF. When I got the call letter, I saw they had got my birth date wrong. Determined not to lose out on a good opportunity due to this technical error, I decided to leave for Delhi immediately to get it rectified. I was confident that once this was done, I would get the job.

I got on the general compartment of the Padmavat Express. The crowd was crushing, but I squeezed myself into a corner seat. Preoccupied with thoughts about the future, I was startled when some four or five thugs gathered around me and started pulling at the only thing of value I had on that day- a gold chain gifted to me by my mother. Criminals getting on in general compartments in U.P. is, believe it or not, quite common. Being a single female traveler, they thought me an easy prey. When I refused to hand the chain over, they started coming at me one at a time. I kicked, punched and fought as best as I could. For a brief moment, it even seemed I had the upper hand. The compartment was full of people, but no one came to the rescue of a girl being robbed and attacked. Since they couldn’t take me on one at a time, each grabbed a limb and hauled me out the train. I flew into an oncoming train and the force threw me onto the opposite tracks. What happened thereafter took a matter of seconds. Before I could move my left leg off the track, a train went over it.

Much later, when Mahila Ayog demanded a report, it was discovered that 49 trains had passed me by as I lay wrecked and bleeding on the tracks. Rodents would come and feast on my oozing wounds, scampering off when trains came. I kept screaming in pain before finally passing out. Looking back, I really wonder how I managed to hold on for so long. I never thought I would survive that night. But when morning dawned, renewed hope surged through me. Open tracks transform into public toilets for poor villagers who have nowhere else to defecate. The next morning when the lads came to take a dump, the sight of my mangled body greeted them. I was to be taken to the Bareilly District Hospital. But the move involved so many bureaucratic hurdles from disinterested government employees that I was left on the platform for hours before being taken to the hospital.

My leg had to be amputated from below the knee immediately to prevent gangrene from setting in. I was losing blood alarmingly. Here then I was informed that the hospital was out of anesthesia. With no choice, I instructed them to go ahead with the amputation. The limb was sawed off while I was fully conscious. The hospital staff were severely encumbered by the lack of supplies, but did everything in their power to make my suffering lessen. The pharmacist B.C. Yadav donated his own blood because there was none to spare. To give you an idea of the kind of hospital and place it was, I need to mention this. After the amputation, as I lay in the OT, a street dog ventured into the room and started feasting on the leg that had just been removed from my body.

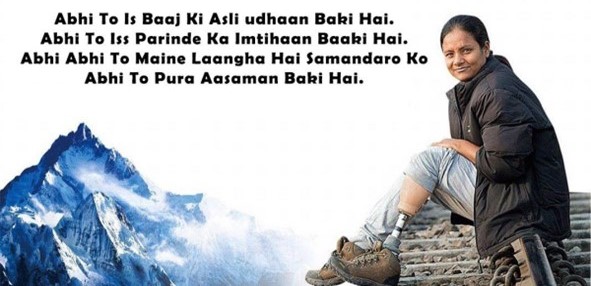

Lying there on the hospital bed, when I was at my weakest and most vulnerable, I felt helpless to defend myself and my family against this onslaught. I said to no one in particular, “Today is your day. Bark whatever you want. But someday I will prove, without a doubt, the truth of what happened to me.” My left leg was amputated. A rod was inserted in my right leg, from knee to ankle, to hold the shattered bones together. I pondered on the most impossible dream I could set for myself. I decided to climb the Everest.

Every girl cannot climb the Everest to prove herself right. But for me it was never a choice. The public imagination had reduced me to either a victim or an attempted suicide case. This was the only way I could reclaim my voice. When I tried to tell my doctors about my plan, there were two reactions. If I tried to discuss my plan with anyone, either I was laughed off or told that trauma had affected my mental health adversely.

Usually amputee patients take months, or even years, to get accustomed to their prosthetic limbs. I walked in two days. The mind holds tremendous sway over the body. Once I had decided that this is what I would do, I let nothing get the better of me. Straight out of the hospital I went to see Bachendri Pal, the first Indian woman to climb Everest. Aside from my immediate family, she was the only person to not dismiss my mission. But she didn’t sugar coat it either. She told me, “In this condition you made such a huge decision. Know that you have already conquered your inner Everest. Now you need to climb the mountain only to show the world what you are made of.”

My prosthetic limb posed some unique problems. The ankle and heel would constantly swivel as I tried to climb, causing me to lose my grip often. My right leg was held together by a steel rod. Any pressure sent up spasms of acute intense pain. My Sherpa almost refused to accompany me, assuring me that I was on a suicide mission. Most regular folks don’t stand a chance against the mighty mountain. What did I stand?

Every climber has to traverse four camps on route to the peak. Once you’ve reached camp four, there’s 3500 feet to the summit. This area is known as the death zone, notorious for the number of lives it has claimed. There were bodies of erstwhile climbers strewn all around. A Bangladeshi climber I met earlier breathed his last right before me. Ignoring the cold fear in the pit of my stomach, I trudged on. Our bodies behave according to how we think. I firmly took stock of my fears and told my body that dying was not an option. But all that changed once I reached the summit.

On 21st May 2013 I reached the Everest summit. Earlier My Sherpa had informed me that my oxygen supply was critically low. “Save your life now so that you can climb Everest again later,” he said pragmatically. I said, “If I don’t climb Everest now, my life will not be worth saving.” I erected the flag of my country on the peak, deposited some pictures of my idol Swami Vivekananda next to it. Then I used the last vestiges of my oxygen to take pictures and videos of myself on the peak. I knew I was probably going to die. So it was important that the visual proofs of my achievement make it down to the world. Fifty steps later, my oxygen finished.

I have little patience for wonders of faith, destiny, kismet and the like. We chart our own destiny. It is my firmest conviction that luck will favour those who have the drive and the tenacity to win. As I lay suffocating and gasping for breath, I came across an extra cylinder of oxygen. My Sherpa quickly latched it on me. Slowly we embarked on the precarious downward climb. Far more deaths occur on the downward climb than the upward one on Everest and now that I had survived the worst, it was time to tell my tale.”

I am Dr. Arunima Sinha, the world’s first female amputee to climb Mount Everest and that is my story.

“I really think a champion is defined not by their wins but by how they can recover when they fall.”

– Serena Williams

অসীমদা

অনেক ধন্যবাদ।

ডক্টর অরুনিমা সিনহার লেখাটি চমতকার।

এই পত্রিকা তোমাদের সুন্দর এক উদ্যোগ। সকল লেখককেও ধন্যবাদ সুন্দর সুন্দর লেখা গুলোর জন্য যা অনবদ্য।

She had tremendous courage to reach the goal. Write up is really spell bounding.

Excellent. We,women are so proud of you. This is an incredible and very inspirational story. I am ashamed to have read that noone came to your rescue after this horrific incident.Your experience is horrendous but you overcame everything with your sheer determination. Kudos to you.